When most people hear the last name Bowser, they immediately think of Muriel Bowser, the long-time mayor of Washington, D.C. But one of her brothers, Marvin Bowser, has an impressive resume of his own.

Born and raised in D.C., Bowser served in the U.S. Air Force as an intelligence officer for nearly 10 years. While his military career gave him significant fulfillment and opportunity, the consequence was that — as a gay Black man serving under Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell — he couldn’t exist as his authentic self.

Bowser separated as a captain after duty stations ranging from the European theater to the Pentagon. He settled back in D.C. as a new veteran just after the peak of the AIDS crisis, where he spent six years working as a civilian for the Navy and 18 years as a defense contractor. While Bowser still didn’t feel comfortable being out at work, that doesn’t mean he didn’t do the work elsewhere. He came out as gay in his private life, joining D.C.’s Black Pride movement and connecting with the local queer community.

As the years passed, Bowser found a passion for documenting the community’s rich history. Last year, after realizing that the history of D.C. Black Pride is poorly documented, he produced a TV documentary special, DC Black Pride — ANSWERING THE CALL. His goal was to capture the stories of leaders, many of whom are personal friends, while they are still alive. At D.C. Black Pride this year, Bowser hosted an event and screened his short film, BlackHair, which he describes as his love letter to Black culture and documents the making of his photography exhibit all about Black hair.

In the spirit of capturing stories, we interviewed Bowser about his life as a gay Black veteran with strong ties to D.C.’s Black Pride movement and how he’s fighting today’s efforts to erase his community’s history.

Emily Starbuck Gerson: Why did you choose to join the military?

Marvin Bowser: The military chose me! I was going to figure out my road to college myself. When I was applying for colleges and scholarships, I was offered an Air Force ROTC scholarship. I really hadn't thought much about the service before then, but I really liked the idea of not going into debt for college and having a path to a career afterwards.

ESG: You joined in 1983, when open LGBTQ+ service was banned; did you already know you were gay?

MB: No, I made that decision to join the military while leaving high school. My realization about being gay happened during college, before commissioning.

I really liked my experience with ROTC and the seriousness and the focus of the military, so that's what I wanted to do.

ESG: Was it a struggle to hide your identity as you served?

MB: It was interesting because my first duty assignment was an air base; there were lots of young officers my age that I hung out with. I was not in a relationship, but I had friends and we got to do a lot of travel and eat and drink our way across Europe.

But you know, at the same time, that was during Don't Ask, Don't Tell. So when they caught homosexuals, that was a big deal, and enlisted people were usually given dishonorable discharges, officers could be charged and locked up at Leavenworth. If they got the entry into a “ring of homosexuals,” they would go after the most senior people hardest, so that was not good.

ESG: I've heard many people say how hard it was to compartmentalize a major part of their identity. Was that a difficult weight to carry?

MB: I was focused on the mission. This was during the Cold War with the Soviet Union and we were busy. I worked hard. I kept my private life private.

The rules were that you don’t ask, you don’t tell. But if you unpack that, what does that even mean? It meant you don’t announce your sexuality. I guess that gave you room to be a good soldier, but people could also out you.

At the same time, I served with people who were easy to perceive as gay, but who were super troops; they did the work and got respect, and they were who they were. I had a base commander whose “personal friend” was a lieutenant of the same sex who was often parked in front of her base housing. They weren’t telling, but I guess no one asked. The base commander was a full colonel, and I bumped into her years later, still in uniform, still doing her thing.

But here’s another story. I was a security officer at my second command and a young airman disappeared for like a week, just gone. When he came back, he said, “I want to get out of the Air Force because I'm gay.” There were things that I had to do as a security officer, but my expectation was that he'd be quickly gone because he came in and he told.

The response from above was the opposite of what I expected. It was, “How do we know you're gay? You're not just getting out.” It was like he had to prove something. It was weird.

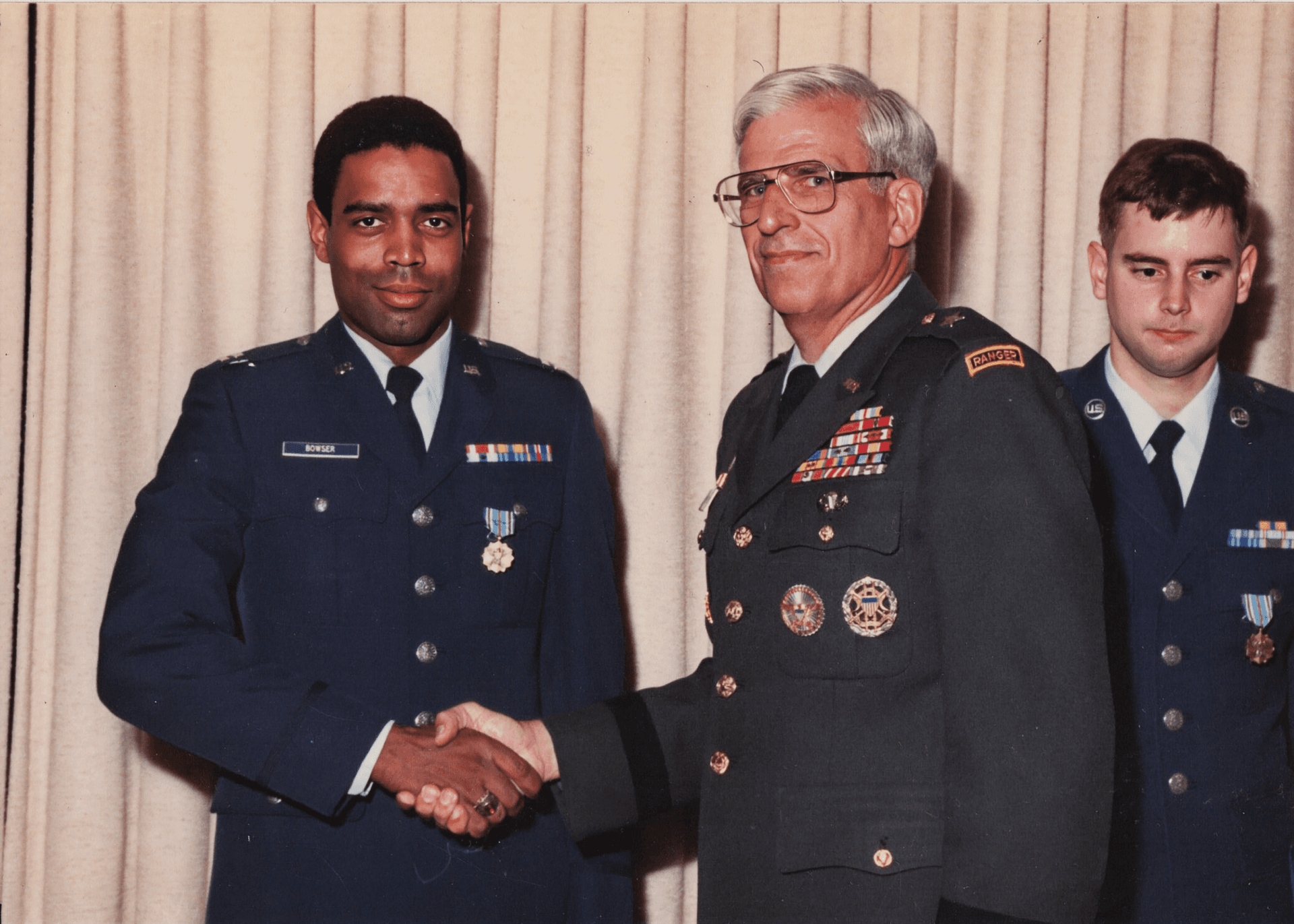

Captain Marvin Bowser is receiving his Joint Staff designation from Navy Captain Harrington

ESG: That is odd; I’ve heard such a wide range of stories. It seems everyone’s experience under Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell was so different depending on individual commands and colleagues.

MB: I think that's key. There's a measure of who you are, and then it's who is around you. And, yeah, if they know you as a person, then maybe it's not a problem — or maybe it is. Because every day, you’d discover that somebody you thought was your good friend isn't, and that's how we find that out.

ESG: I feel that since my wife is a trans service member getting kicked out. The irony for her and so many of our friends is that their commands and colleagues love and respect them and don’t want them out. It's outside forces saying there's a problem.

MB: Right, I mean, none of those current situations came from the military itself.

ESG: Were you able to be open about your identity and get support from anyone while serving?

MB: No, I told none of my friends at the time. But later, when I got to the Pentagon, one of the people in my office was also at the first DC Black Pride as I was. We've been friends since and came out to each other. And then the lieutenant colonel we worked for was also LGBTQ. I bumped into him at a gay bar in DuPont Circle.

ESG: When you left the military in 1992, how was your transition out?

MB: I had an easy transition from active duty Air Force to working for the Navy as a civilian and then working as a defense contractor, so it wasn’t a hot and cold thing.

One of the things I wanted to do before I left the military was complete my master’s degree, and I did not do that. When I started working for the Navy, I told my division head that I wanted to start my Masters but might need to leave early a few days a week. He said “Sure, that’s no problem, and we’ll pay for it. There's a training budget no one is using.” So I did that!

That worked out well for everyone, because they were doing a major telecommunication modernization across the Navy for intelligence, and since I had a master’s in telecommunications, I led that. I developed the solution to do video teleconferencing from shore to on ships at sea at a classified level. So I’ve done some cool things that benefitted the nation.

ESG: That’s incredible. Is there anything you look back on with regret about your military service or transition out?

MB: My transition out was positive; I don’t regret it. What I regret now is how the military has been politicized.

I think the way the United States has survived and thrived this long is due in part to the separation of the military from politics. And now the politicization of the military is going to have unforeseen negative repercussions.

ESG: You’ve said publicly that even after leaving the military, you felt unable to be your full self as a civilian in the defense industry. What caused you to feel this way?

MB: It's because I continued to work in heavily military-like environments. Most of my co-workers and all of my clients were military.

And those environments were hyper-competitive. As a Black man, it's like adding more reasons for them not to move you along or not to give you opportunities to excel. I couldn't see how that was an advantage to me.

Captain Marvin Bowser shaking hands with General Partlow after receiving his Joint Staff Badge.

ESG: On that note, did you experience racism or discrimination while serving?

MB: Yeah, there were two very clear times, and they weren’t microaggressions; they were big things.

The first time was when I wanted to become an Air Force pilot. Near the end of the first two years in, I submitted for flight school with the new base commander’s endorsement on my application. Step one: a medical screening. That package went from a base in Germany to the headquarters in St. Louis and back to Germany in one week. This is before the internet, so it was physically reviewed and traveled across the ocean twice in a week. When it came back, I was a 1A, which meant I couldn't be a pilot, but I could be a navigator.

The one issue they cited: My right eye was 20:50 and was correctable to 20:20 with glasses. I knew plenty of pilots who wore glasses. I'm not a backseat kind of guy. I didn’t want to be a navigator. I saw that as a career-limiting job.

The second time was when I got orders for my next assignment. As an officer, there’s a progression; you want to get that unit experience, then you need to go to headquarters, and so on. I had done my unit time right at the beginning. Now it's time to go to headquarters, and they wanted people to stay in Europe. Our headquarters was 20 or 30 minutes from where I was currently living. So this is a no-brainer, right?

I got the headquarters assignment, but not really. I was sent to a detachment that was literally in a German national forest in a bunker. I didn't think anything of it until I got there and saw it's a small unit with a few officers, and there are already three Black officers there. And I’m the fourth. We had a new NCO coming in at our support base, and he was Black as well. I was like, there are a lot of Black people in this small unit, right?

Then when I went to headquarters, I noticed there was one Black officer and everybody else was white. And not just white, but I mean, blonde hair, blue eyes. It looked like an albino colony. It felt like this was not accidental. So it's like they’re giving us orders here and then they send us all out to the woods, literally, while headquarters is lily white. It was crazy.

ESG: That’s like something from the movie Get Out! Did you or anyone else ever share concerns or discuss it, or it was all unspoken?

MB: I just felt like that was going to go nowhere because the people I could speak to were not in a position to change it. They're getting orders there too. Our job is to do the best job we can, you know, to satisfy the mission. So that's what we were doing.

ESG: That makes sense. Given all of these struggles, do you feel like serving still had positive impacts on you?

MB: Oh yes, for school and the career path after. A lot of my friends in their junior or senior year in college were freaking out, but I knew what I was doing.

I also got one of my top location choices and got to go to Europe and do a ton of travel. I love cultures and wanted to learn another language. Name me a major ski resort in Europe, I've skied it. It was a cool way to get started.

In life, I've been able to build on everything I've done along the way. That was a great foundation and way to get started instead of going to college and then doing some stutter steps for a few years. I kind of hit the ground running and I was exposed to technologies early on that I did not know about before. I discovered a love of technology and moved forward with that.

ESG: My wife and I also really loved our time stationed in Europe. Were you living in Europe or the U.S. during the AIDS crisis?

MB: I came out when AIDS hadn't quite been named yet, so it was early on. Then I was in Europe for four years, and AIDS was worse in the States. By the time I got back, there was treatment for it, but there were a lot of people still sick and dying.

A lot of the group that was hit hardest are a few years older than I am. So I know a few people who died from AIDS, but friends of mine who were older were the ones whose friend groups were wiped out. So I didn't have that experience, thank God.

ESG: I know you were involved in the early days of D.C. Black Pride, which focused on the AIDS crisis. What inspired you to get involved after spending years in silence?

MB: It gets to a point where enough is enough, and you've got to get out there. I found that coming out is just a weight off of your shoulders. There's freedom there. You get tired of looking over your shoulder all the time. It's like, this is who I am. If you don't like it, you do you, boo.

I got to know some people socially who had been amazingly involved in fighting AIDS. Not just that but uplifting and providing support for people who are sick with AIDS and HIV who had no other support system.

That was my motivation to do my documentary about DC Black Pride. These stories had to be recorded. I wanted to celebrate my friends; people I have been fortunate to know, who did that work and who are still with us.

ESG: It sounds like a lot of mutual aid was needed to survive that time.

MB: One hundred percent. And there was still so much racism in the LGBT community. Whitman Walker was up and running then, but a lot of Black people didn't feel comfortable going at the time. So the community became Black men and Black women taking care of our own.

Marvin Bowser during an Art Talk/Art Walk at the Mount Vernon Triangle in Feb. 2025

ESG: Absolutely. What do you think makes D.C. a special and unique place for someone living at the intersections of your identities of Black and gay and veteran?

MB: Well, there are a lot of people like us here. Washington is a place that people come to study and come to work and find their tribe here and stay. There was a vibrant black gay culture, and within the other cultures here.

You can be gay, have a meaningful career, have a house, and you can do all the things. People come here and then they discover Washington while they’re here and stay.

ESG: We’re also witnessing the erasure of history, especially Black and queer history. What do you want the younger generations to understand about the time we live in and your experiences?

MB: I’ll say facts matter, so know the facts. Everyone is playing free and loose with these narratives that aren’t based on anything but “I just thought this up a minute ago.” So do your homework and know the facts, because facts matter.

To follow that up, tell our stories. Document them, because as we’re seeing, bastions of history are being edited and destroyed. That’s unacceptable; it’s crazy dangerous.

And as you know, the trans community is being scapegoated, and it’s a test case. So they have them and then go after everyone else. Then they have marriage equality as an issue again. Their agenda is lengthy.

ESG: Yes, it feels like everything’s rolling backwards.

MB: Yeah, and everything’s also cyclical. We’ve been here before, and we’ve survived.

In the Black community, a lot of the artifacts that survived til today from slavery are because families kept those artifacts and protected them and handed them down through generations. And they thought it was safe to bring them to an institution like the National Museum of African American History and Culture. To have the politics again go in and edit — that is horrible.

ESG: I know times are tough right now, but is there anything that gives you hope about the future or today’s Black LGBTQ+ youth?

MB: That’s a good question. During Black Pride this year in World Pride, there were a lot of young people who were very free and expressive just living their lives out loud — and there are all these other forces trying to tamp that down.

A lot of people went through a lot of pain and suffering to get to the point where young people could be who they are now. We will not go back and it’s not going to be easy, so we’re back to fighting.

I think a way to help foster that is for the generations to lock arms and share tactics that worked in the past, because we’re right back to doing the same things again. The young people can better leverage the technologies, networking, and getting the word out that work now that wasn’t available.

As you know, for this LGBT Black history project, people are collecting programs and minutes from meetings because that’s how we did it, and that’s still around. It’s amazing that people kept that, because it was important. Otherwise it was like, what happened, did we just fall out of the sky? No, that’s not how that works. Let’s not lose that as we weather this storm together.

This interview was conducted by Emily Starbuck Gerson, special issue co-editor, award-winning journalist, and former Modern Military staffer. She currently resides in the DMV with her wife, a trans service member facing separation.