Soldier, DJ, leader: SFC Sharla Murrill opens up about resilience, representation, and life beyond the uniform.

Sergeant First Class (SFC) Sharla Murrill, a North Carolina native, has been serving in the Army since 2002 and has resided in the DMV since 2019. After beginning her career in active-duty service, SFC Murrill is now a member of the Army National Guard, serving on the National Guard Bureau Joint Staff in Arlington, Virginia.

SFC Murrill is a highly-decorated soldier with three peace-time operations and three combat deployments under her belt, along with a bachelor’s degree in sociology.

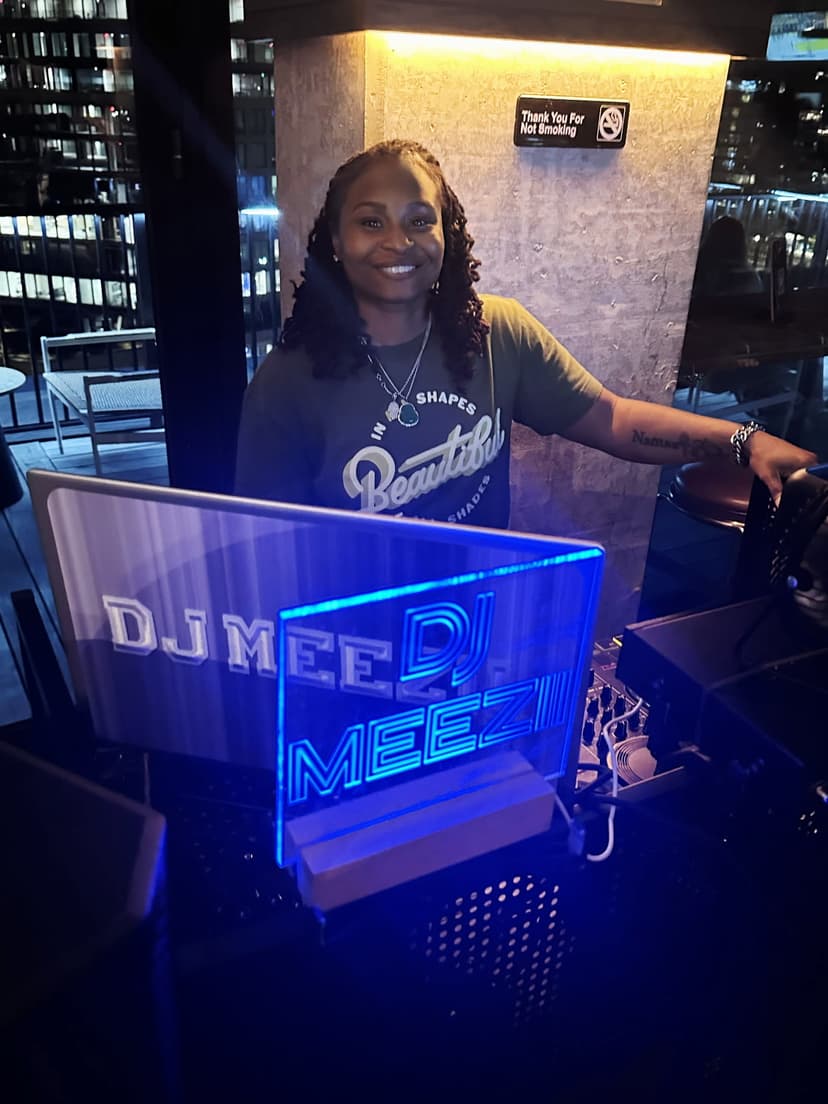

During her spare time, Murill is a local DJ with a regular gig at the Thompson Hotel located in the Southeast Region of the District of Columbia.

We interviewed SFC Murrill to learn where she finds community in D.C., how she’s navigated serving under difficult policies, and her advice for other Black queer service members or veterans.

MaCherie Dunbar: You’ve served in the military for 23 years. Do you have any plans to retire soon, and do you think you’ll stay in the DMV?

SFC Sharla Murrill: I have 3.5 more years until I plan to retire. I’d like to make E-8.

I think I’ll stay here. I’m from a small town, and I like the movement here. There are more opportunities, I like the people, and I enjoy what I do. I also think I’ll have more opportunities in the civilian sector once that time comes.

MD: Have you found community at the intersection of Black, queer, and military or veteran?

SFC Murrill: Most of my community is in the military, but I have developed friendships outside of the military; Black, queer, all types of people and musical genres. Most of my circle is Black, queer, and active duty.

I don’t come across too many veterans because I don’t think most people know I serve in the military. I look very different outside of uniform. Hair down…[swag up]. I think it’s the same for a lot of us; we look different.

MD: Do you think there’s something the District could do better to support the community at the intersection of Black, queer, and military/veteran?

SFC Murrill: I think there could be more lounge events that allow people to truly connect. I don’t see enough events anywhere [in the District] that support that type of community that isn’t a party or club environment.

MD: You’re right, there is a gap in activities that don’t revolve around alcohol or loud music. There is a very niche scene for the Black queer community, especially as it pertains to women, because we don’t have our own establishment.

On another note, like me, you served during Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. How was transitioning out for you, seeing the pivot in policy and finally being able to be out and proud?

SFC Murrill: I was on active duty during that time and had to process packets where people were getting put out for being exposed. That was crazy to me, and scary. I just couldn’t believe it.

It was a hard and slow transition, honestly, because you get so used to suppressing who you are. Once Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell was done, I think people of the old-school era, like myself, had a difficult time being out and open because of the culture around us. We hadn’t had any training, initially, so you still had people around you talking badly about gay people, and that they just couldn’t understand why it was repealed. It was almost like you were still living in it even though you were free.

Once we did get the training, the mindset began to shift. Sometimes you can be raised one way, and your train of thought is only how you were raised. You don’t know how to think like an open-minded person. You go with what you know.

The military did a good job with that kind of training, so people could get adjusted. It’s policy, so now you have to be careful what you say. People have their personal opinions, but they don’t voice them

I eventually came to the point where if someone were to ask me, I would tell them, but I didn’t shout around the office, “Hey, look at me! I’m gay!” Now, no one cares. People have stickers and flags at their desks, so there’s nothing to ask anymore. Even our allies represent us as allies.

MD: I always said just because the policy shifted, it doesn’t mean the ideology shifted. To see the kind of growth and transition more than a decade later, where people aren’t afraid to out who they are on display, is incredible.

Sadly, we’re currently seeing some reversals of progress. How do the constant threats and changes, with relation to federal policy, influence your feelings about serving?

SFC Murrill: My professional feelings are that there are going to be policies in place that you may not necessarily agree with, but I also understand there’s nothing I can do about it. When you’re in this uniform, everyone is your brother or sister, and that’s just that. If you don’t want that, you can get out. This is totally voluntary.

With the trans ban, for example, I don’t like it, but it’s more powerful than me. It does dampen the morale, especially for those of us who may have trans peers, because there’s nothing you can do to help them. It’s sad that we have bigger problems going on in the world, but this is the highlight.

MD: You’re 3.5 years from your retirement goal, even though you’ve already reached retirement qualification. Many with over 20 years have begun dropping their retirement packets, as one does, but especially with the change in administration. You seem committed to service and achieving your goals, regardless of what may come from the top down.

SFC Murrill: I have too much time invested to throw it all away based on things I can’t change.

Outside looking in, I’m trying to get to the point where I can put on civilian clothes and be more active and outspoken without being penalized.

MD: I’m glad you brought up voting. Were there active conversations to ensure everyone was voting, or was it like the military I remember where you just don’t talk about it?

SFC Murrill: There are certain things that you shouldn’t talk about at work; they call it office decorum.

But on the outside, yes, my peers and my friends, we were having conversations and making sure people were looking at policies to understand what’s going on in the world and taking care of each other when it comes to voting. Making sure everyone got their absentee ballots in, things like that. And we were given time to go vote on election day.

MD: If you had any advice for any incoming young Black queer service members, what would it be?

SFC Murrill: You don’t have to go around announcing to the world, but don’t be afraid to be your authentic self. Build different communities around you, safe communities, that you can talk to and trust.

Just because you see another person in uniform and they are your brother or sister in arms doesn’t mean you can trust them on a personal level.

Do what you came to do when you put it on. Go for as much as you can to be as powerful as you can, regarding rank, so that you can make decisions and be part of the community that enforces policy and affects change.

Take those classes to be certified as an EEO rep, for example, so when you’re in uniform, you can report violations. We shouldn’t still be in times where we’re being discriminated against for being queer or Black, but it still happens.

MD: If you could do it all over again, would you?

SFC Murrill: I would, yes, but I’d hope that if I did it, then policy would be different, because Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell was very difficult. I am so thankful to President Obama for making the change and opening a very huge door for marriage equality. We were progressing as a nation. We knew there was going to be a culture change. It needed to happen.

This interview was conducted by MaCherie Dunbar, special issue co-editor and guest contributor, an award-winning advocate, and Black queer veteran residing in Washington, D.C. Make sure to read her personal story in this issue.